An orange shoebox of drugstore prints

I remember discovering a glossy orange box of drug-store color prints, jammed overfull, stuffed with the condensed photos of my father’s life. They were high up on a shelf in the back of the entryway closet of my parents’ home. I eagerly pulled it down and started flipping through undersaturated, fading color snapshots. Even the negatives had started to fade.

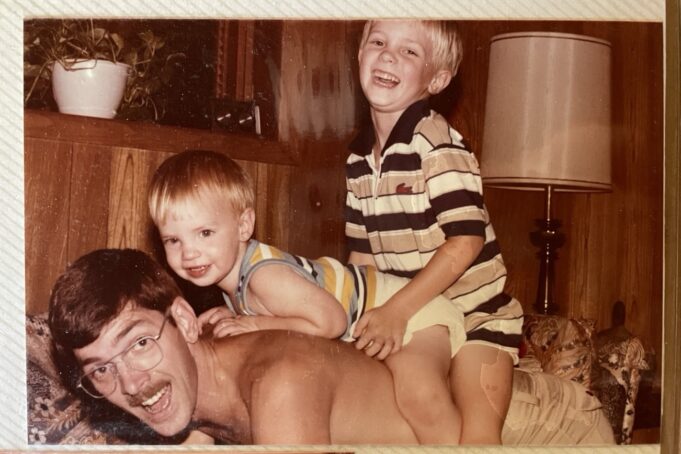

My father died when I was young and these had likely been in the box since then. I knew sunlight was bad for photos but these hadn’t been in the sun and yet they were still fading away. The contents of a half lifetime of moments, crammed into a shoebox in the back of a closet. And even then they were fading away.

I had already begun to save my photos in similar shoeboxes piling up in my closet, labeled by year — the accreted evidence of my own photography practice. I carried them around with me for a while, shifting them from closet to closet when I moved. But after finding the orange box, I started the long process of making digital scans before my own prints and negatives started to fade.

A black box of silver halide prints

I remember finding a matte black, two inch thick, box at my grandmother’s house. It was filled with black and white 8×10 silver halide prints. These prints are made by exposing the negative to a timed blast of light through the negative on a kind of reverse camera called an enlarger. In the darkroom, the paper serves as the film in this operation. Little photosensitive silver halide crystals in the paper absorb the light but don’t start to change until you submerge the paper in the developer chemical. Then you can see the ghostly images slowly grow in contrast under the red light bulbs who don’t effect the paper. Next you move the print to the stop bath to stop the developer from further darkening the print. Finally a couple minutes in the fixer to freezes everything in place and preserves the print you made. Hang it up to dry and these photos can last over 100 years.

My grandfather had shot and developed these in his home darkroom. A lifetime of photographic practice collected into 100 prints in a matte black box. I flipped through them hoping to learn about this other man who died before I got to know him, let alone share his love of photography. I expected his prints would have held up better. But whether it was the home mixed chemicals or something about his process, these photos too were fading.

Hard drives are sand paintings

I’ve been taking photos intentionally since 1999 when I was a senior in high school and won a local contest with a photo of a Lynyrd Skynyrd tape in a drainage ditch. For the last 17 years I’ve shot mostly digital. And in the past few years I’ve shared nearly six thousand of them on Instagram. I flip back through them sometimes when I feel down and remember the good times I’ve had. But it’s a solo, private review.

I often wonder what my family will find of my work when I die. They won’t find any shoeboxes. And if I’m not careful they won’t find any digital files either. Hard drives are like sand paintings: the slightest electrical or magnetic breeze can destroy them. Even if the digital media survive there has to be software left to read the particular file formats they are saved in. No one will find my photos in the back of a closet.

I once joined a conversation among librarians and engineers from Google about the most reliable way to transmit information across very large long time scales. They insisted that google’s strategy of using hard drives with thousands of copies spread across the planet was the most foolproof plan. Despite social collapse, nuclear holocaust, or natural disaster some copies would survive.

I said then as I say now, that the only proven method for transmitting information across very large time scales is religion. Religion creates text and then those texts create communities around them that reproduce and expand on the text. Without a community to carry your words or art or photos forward through time they will fade.

Telling the family origin stories

This Christmas I’ve been trying to make time to tell the origin stories of our family to our three daughters. Stories of early jobs, dates, international travel, proposals and struggles to find work and meaning. These girls, raised in close proximity with iPhones, keep asking for photos of these formative events. Fortunately I can still pull up most of them as digital scans of mostly negatives I shot before the digital era. “You have to write these down!” My oldest daughter exclaimed repeatedly as we told the stories of the hilarious and harrowing experiences that formed her mother and I.

I used to think I wanted to make my mark on the universe, to prove that I existed and that my life mattered. But that’s a very present focused ambition. Now, I’m increasingly focused on joining my mark to what came before and what will be coming after.

What makes religious or familial communities survive beyond one generation is that the stories they tell and retell help those presently living make sense of their experience and orient themselves in the world in context of a lineage larger then their own life and experience. Either they do this job well enough to get passed on or they fade and are forgotten.

The only way to keep the stories of our lives from fading is by joining them to a larger story that helps those who come after us know a little bit more about who they are and who they could be.

I never got to hear the stories that went with the photos my father and grandfather shot. I’ve had to piece together who they were and who I am with a sparse few stories cherished from family members and a few more stolen from people who knew then and were generous enough to share any memories they had.

The gift I want to give my children is a story, with a some context for the kinds of people from whom they come and the kinds of people they might become.

Photos always fade. But stories can make and re-make communities across thousands of years —but only if they help the hearers make sense of their own lived experience.