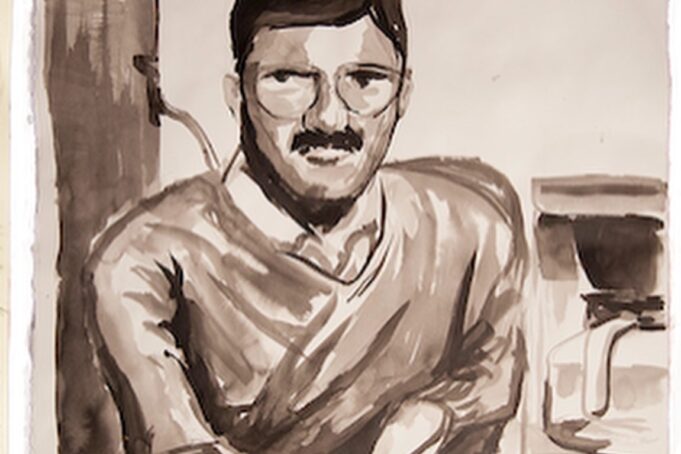

Today is the day that we remember people we loved who died on active duty serving their country. My dad is one of those people. He died in an unexplained crash of an F4 Phantom fighter jet during a training mission. I found the crash site last fall and wrote about it here.

Memorial Day is usually hard for me because it’s a time when people feel free to say what his death and the deaths of so many others mean. And while this is normal, even the purpose of the shared civic ritual, all the losses of people we love resist collapsing down into a single story of serving one’s country and dying for others.

Other losses

My wife, Melody’s, grandmother was a twin. She lost her twin

brother to a plane crash somewhere over the Himalayas in World War 2. She always held out hope that he had somehow survived the crash and had built a life there on the other side of the world. It was the NPR story of another family looking for crashed WWII planes by asking local hunters if they knew of any crashed planes that led me to Arkansashunting.net where ultimately found people who helped me find the spot where my dad died.

When we don’t get a chance to see the body, there’s always a crack of hope for our mind to wonder at. I think this is part of why it was so important for me to find where my dad died. I never believed he survived but I fantasized about it sometimes. His death and life were never as real to me as when I was walking the woods pulling up pieces of airplane, flight suit and boot.

Other stories

My dad did die serving his country. He was on active duty getting trained on the weapons systems in the second seat of the F4 fighter jet.

He also died in the process of transitioning from the Air Force to the Air National Guard: the reserves of the air force. He wanted to take a step away from 80 hour work weeks, spend more time with his parents and sisters, and with us, doing woodworking, gunsmithing and hunting.

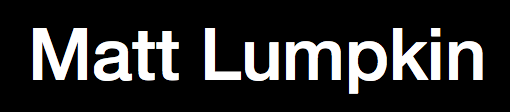

He also died fulfilling a dream he’d had since his teen years of being in the cockpit of a fighter jet. After seeing the Blue Angels at an air show, he turned to his friend and said “I’m going to fly one of those.” And though he wasn’t on the stick the day he died, he did fly one. Even though he wasn’t able to go to the Air Force Academy or take a direct route to piloting due to his need for glasses. When he died, he was actively making plans to build wood and canvas ultralight planes with his base commander. He was a maker and a first principles thinker who understood that direct experience is more reliable than authority.

Even after he transitioned to different dreams of Air Foce ROTC which made it possible to be the first to go to college in his family, he still was obsessed with the F4. He once stayed up all night programming punch cards to make the mainframes at University of Arkansas print out a huge image of the fighter plane made up of letters numbers and other ASCII characters.

Bigger stories

The two leading explanations for the crash are pilot error or mechanical failure resulting in a snap stall at high speed and low altitude. More people familiar with the crash believe it was pilot error. But others I’ve spoken to believe that the crash shares a lot of characteristics with a similar crash of the same model plane from the same lot produced on the same manufacturing line. That F4 had a mechanical failure causing amplification of pilot movement of the stick controlling the bellows that control how the tail moves to make the aircraft turn.

So he may also have died due to a mistake in quality control at McDonnel Douglass. Some have said that the quality control issues plaguing Boeing began after they acquired McDonnel Douglass. So his death may also mean that the captialist need for public companies to grow and grow and grow for their stakeholders inevitably mean that engineers get pressured to go faster and faster and people die as a result.

His service to our country also means that, before he ever climbed into the cockpit of an F4, he was the navigator for one of a relay race of large bombers that flew 24/7 on “nuke alert” for decades during the cold war. These planes and their crews flew in an endless triangle over the arctic circle ready to drop annihilation down on cities full of civilians. This a horror America invented and so far, the American military is the only one to ever unleash such a horror.

His death is, like all our lives, are caught up in the stories of power, war, economics that we are born into and each have to find a way to understand and choose how we will participate in and stand against.

My story

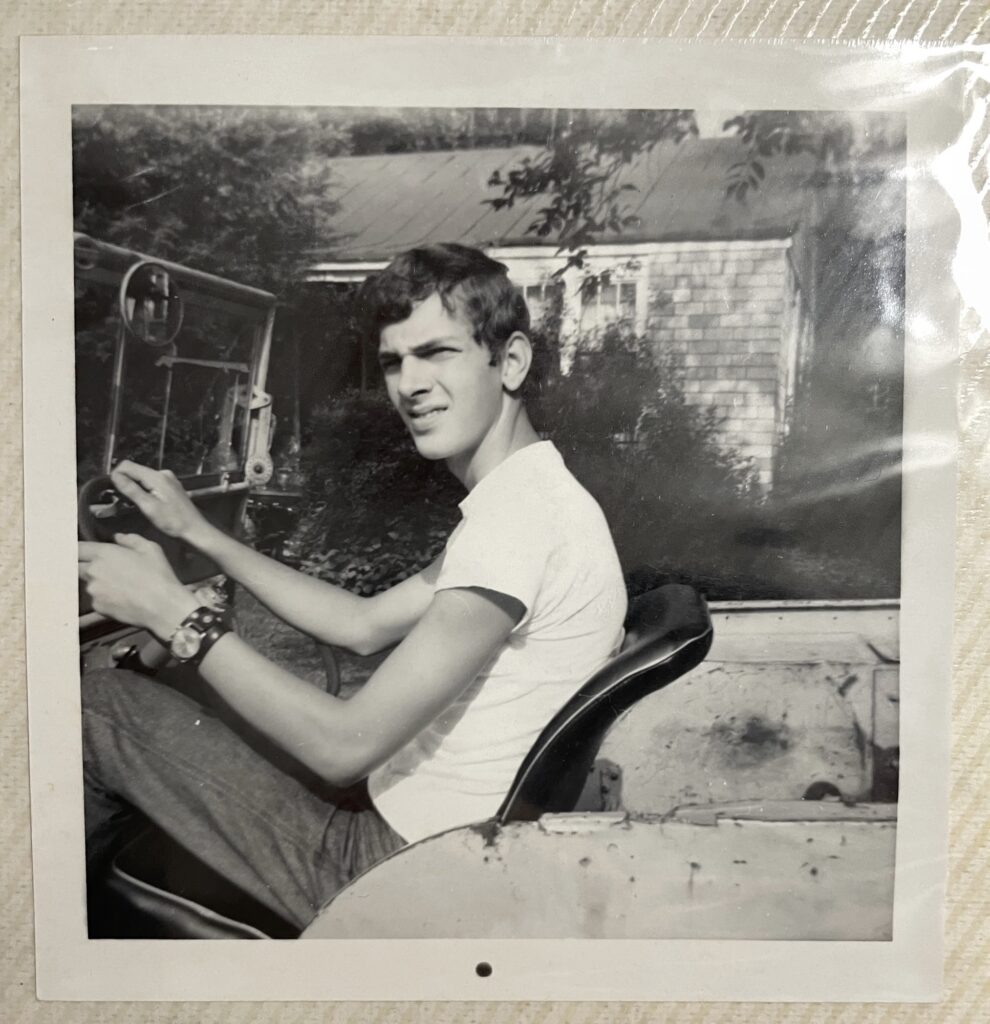

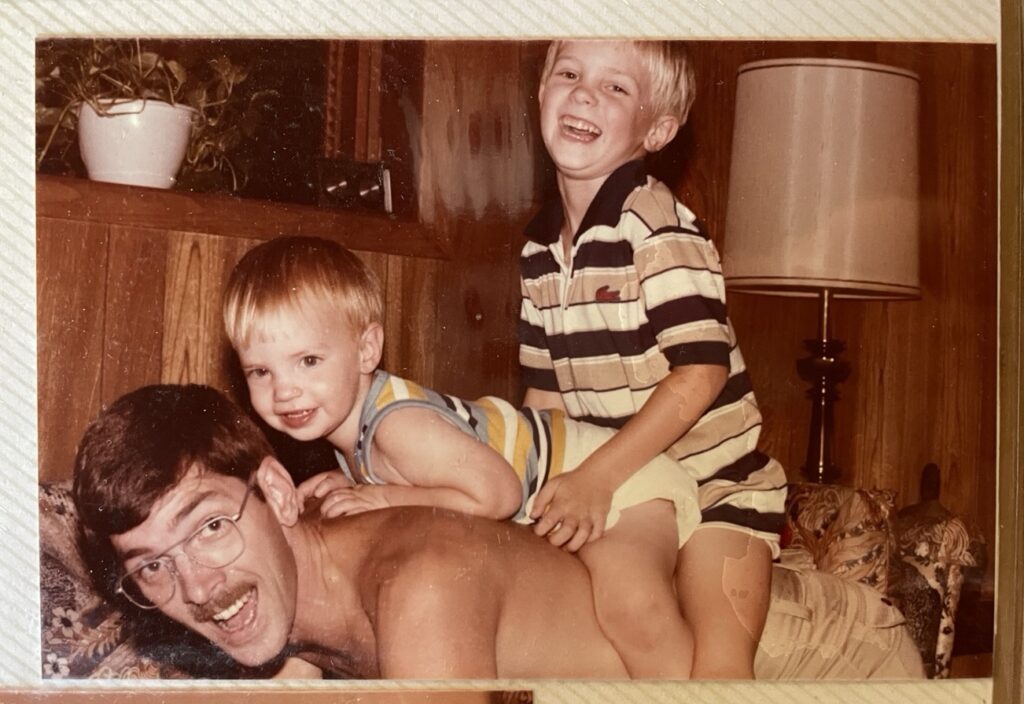

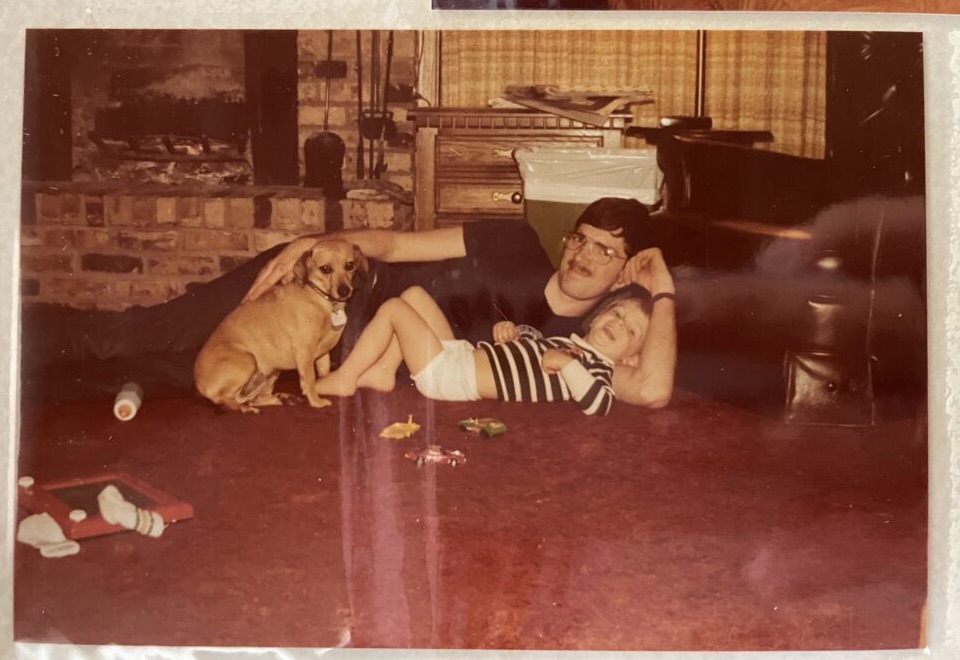

But lately, as my children grow into little adults, one photo captures what the loss of my father means for me. It shows him smiling with joy at the camera, shirt off, with my brother, Jason, and I riding him like a horse.

This photo is so sharp and still cuts me every time I see it. It shows me that I lost a father who loved me and could understand me with the knowledge that comes from being flesh and blood. And yet there are moments in my own life that become illuminated by this loss.

Presence illuminated by absence

On the way home from the dentist

One day, driving home from a hard visit to the dentist’s office with one of my daughters, I felt the weight of the emotional energy I had spent to support her through pain and advocate for her needs with the care team. And as I slumped forward in my seat, waiting at a stoplight, I thought, my father was never there to do this for me. And yet, I get to do this for my children. I reached back and squeezed my daughter’s foot dangling from her car-seat and reached back through time to touch the memory of myself straining to grow up into someone who didn’t need support.

The gift of parenting my children feels like a cosmic do-over to right the wrong of my missing father.

Savoring the beauty

A few weeks ago I was enjoying drinks and chatting with my neighbors on one of their back patios; a weekly happy hour tradition. The kids swing by the table and graze on whatever looks sweet or carby before running off to play together through the evening hours and into dusk. My 9 year old daughter, Hazel, interrupted our conversation to ask if I would push her on “the big girl swing.”

The “big girl swing” is a single strand of climbing rope looped over a high branch in an expansive canopy of an ancient California live oak in our neighborhood. It has a single circle of douglas fir wood for a seat, worn down by wave after wave of children using it. I made the swing when my oldest daughter was about this age. For Hazel, it had been a milestone as a toddler to graduate from a smaller, baby swing to this one.

I don’t always oblige, but this time I heard her reaching out to me with the desire for her father’s strength and attention; something forever out of reach to me, but something I can easily grant to her. I said “I’m enjoying this conversation, but because I care about you, I will take a break and come push you.”

As I stood in the dusk watching her spin and laugh with each successive push, rising up 20-30 feet into the air, pendulum swinging with joy, jokes and chatter rising up from the nearby neighbors, I felt something like what I think my father would have felt had he lived to see my brother and I this age. I felt some part of him in me, alive to this richness and joy.

In this moment, his loss illuminated this goodness, casting a shadow back through time to my own self. I remember learning to push myself on a swing like this, alone by pushing off the tree trunk with my legs. But I don’t remember feeling the power of a grown man pushing me and sharing in my joy and exhilaration. And yet, that night I was both — doubly alive and present to this moment.

Later that night, Hazel came back to the patio and sat by me, laying her body in a chair and her head in my lap. Leaning back, she noticed the bright fingernail moon shining between the eaves of the roofline. Then she said:

“Look at the moon, daddy. It’s so beautiful. We have to savor these moments of beauty in this world because we won’t have them forever.”

I lost my father. And yet what his death means is not simply a sacrifice in service of others, or a casualty of capitalism or the American war machine.

It is the defining tragedy of my life. And, at my best, I strive to live in spite of it and in contrast to it. I try to be the sort of man who pursues dreams other people think are impossible and who is simultaneously interruptible by his children to get down in the floor and play.

And sometimes, I feel his loss illuminating these moments of beauty with deeper meaning and sharpness. And, like Hazel reminded me, I try to savor them.